The Quiet Agreeable Silence of Wanås

- C-print

- Aug 7, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 20, 2025

So, I recently deleted my private Instagram account, one that had served me very well on my path in art for 14 years. It's interesting how surprisingly easy it actually is to be without something you routinely thought life could not, or would not, be complete without. I'm aware there will be losses as a result of this choice, but there will also be gains. Think of it as active noise-cancellation. Instagram had become unbearable, what with frivolous and clout-thirsty content creators churning out things left and right that I had no interest in seeing—none whatsoever—yet were being fed to me daily, per algorithm protocol. This is a very specific moment in time, needless to say, considering the political landscape, and I just cannot abide impressions from random people who seem to live in total and apparent disconnect with the things that are duly occupying my mind. So Instagram had to go. And Instagram had to go for me to be able to safeguard space for thinking and contemplation; to even read books properly again.

"A room of one's own"

It’s in this context that I decided to make an overdue revisit to Wanås Sculpture Park in Skåne, to recalibrate myself back into art mode after a summer largely spent on hiatus from my usually intense art schedule, during which marriage and friends took precedence before my season as a curator soon begins. This trip began at the start of this week, despite the beaches around Lisbon awaiting me tomorrow. As graciously and generously as I am being hosted for a press visit, it’s still an effort. However, I sensed it would do me good. Even before boarding my four-hour train ride, I decided I would write something to encapsulate this getaway. I know it’s not going to be your typical review or guide article offering a potpourri of descriptive impressions about the plethora of imposing art installations found inside the park and on the premises. I think instead of a text slightly freer in form, which will derive from whatever comes to me as I’m there—whether more specifically about the art, the artists, or something else.

I have participated, as the third and only other person (oddly paired at first glance), in a public panel with the art patrons and founding couple of Wanås, Marika and CG Wachtmeister, about art collecting. The couple, who have been collecting art since the 1970s, were honored with an exhibition, Hjärtahärna, at Liljevalchs Konsthall last year, highlighting through their gaze and personal collecting a time capsule of where contemporary art has been, and when. As the public sculpture park—a parallel venture—turns 40 next year, it currently holds roughly 80 permanent artworks by both local and international artists.

Per Kirkeby

I’ve been before, yes, but as I arrive, I’m struck by how incredibly the place looks like the natural set of a Julian Fellowes-style period piece and costume-drama offering. The castle very much looks the part, and everything is so neatly maintained. I even get to stay in what is called the West Wing of the castle. Now, that’s a vibe. As I text in real time with the love of my life from across the Atlantic, we survey a Wikipedia page that further enhances that Julian Fellowes atmosphere, with a history of earls and counts that is still intact. To contrast this, I observe the presence of evident youth and BIPOC individuals among the staff and make a mental note of this as a good thing, on a site that under other circumstances could have offered a completely different optic. Let’s just say, politically speaking, Skåne—apropos my earlier reference to the political landscape—is quite a contrast to my home turf, Telefonplan in Stockholm, with its socially left-leaning values.

Wanås very much is on the Swedish art map. If you are in art, or are an aficionado, you will know it. If you also are lucky enough to have a habit of spending the summer in this region, for whatever reason—family or otherwise—chances are Wanås is part of your annual summer plans; that one token visit to the park will likely happen. This is the closest you’ll get to a Dia Beacon (Upstate New York) feeling in Sweden. There is a faint sense reminiscent of what you feel when arriving at Louisiana, outside Copenhagen..

Jacob Dahlgren

Certain mediated views from the park have managed to transcend beyond the art territory. Swedish abstract pioneer Jacob Dahlgren’s instantly recognizable colorful, Tetris-brick-like installation has in the past been spotted from time to time as a backdrop for people’s Tinder profiles, and on even more salacious apps. Not bad. It does speak of reach. The park and its impressive art artillery, much like the Wachtmeisters’ art collection, point back to where art has been—not always to where art is now. I would have been (and was) much more intrigued, more than ten years ago, to take in the works of artists like Jan Håfström and Ann-Sofi Sidén, who were once (and to some, still are) important figures in Swedish art. Meanwhile, I beam with pride on the inside learning that Bangladeshi-British abstract sculptor Rana Begum is part of the collection. Rana Begum! I partially started this online magazine with my twin brother to have a platform to write about art where our parents’ native Bangladesh is concerned. A characteristic architectural pavilion by Dan Graham—convex or concave, drawing in the trifecta of art, architecture, and viewer—has almost always been an arresting sight for me. Roxy Paine, however, was a moment in time when white male artists still ruled the international art world. Even seeing Roxy Paine’s name feels like being served a madeleine (Proust-style), taking me back to a time when artists had names like Dan Colen, Dash Snow, Banks Violette—rock star male artists.

Robert Wilson

Wanås is like an art history book: when you crack open the same book a few years later, things that didn’t resonate with you at a certain point might now be your takeaway. When I first came here over 10 years ago, I had little idea who Edwin Denby was—the celebrated late American dance critic, once a dancer himself. But it just so happens that a collection of his texts—That Still Moment, published by David Zwirner Books—has recently made its way onto our bookshelves at home. I’m delighted to realize his good friend Robert Wilson, who only just passed away, made his work A House for Edwin Denby in the year 2000—25 years ago—to commemorate his friend. Side note: I’m so happy I had the chance to see the monologue Mary Said, starring Isabelle Huppert, directed by Robert Wilson at Dramaten in Stockholm. That might very well have been a stage thrill of my lifetime. Wilson’s work honoring his good friend is haunting: a slim house skewed in proportions, devoid of visible human presence but broadcasting the voice of someone. It appears to be the voice of Wilson himself, reading from the last book Denby read in life while spending his final days in Wilson’s home. Apparently, Denby had turned to Wilson at one point and expressed being through with life. I can’t quite shake it off. It’s so beautiful in concept. When you are in love, as I am, you are in love with life and with time, the time that is now. I’m turning 40 this year and think of mortality more than I ever have; sometimes imagining myself and my loved one when we are older, say 40 years from now. I wonder what we will look like, how we will talk, and how scared we might be of losing each other to time.

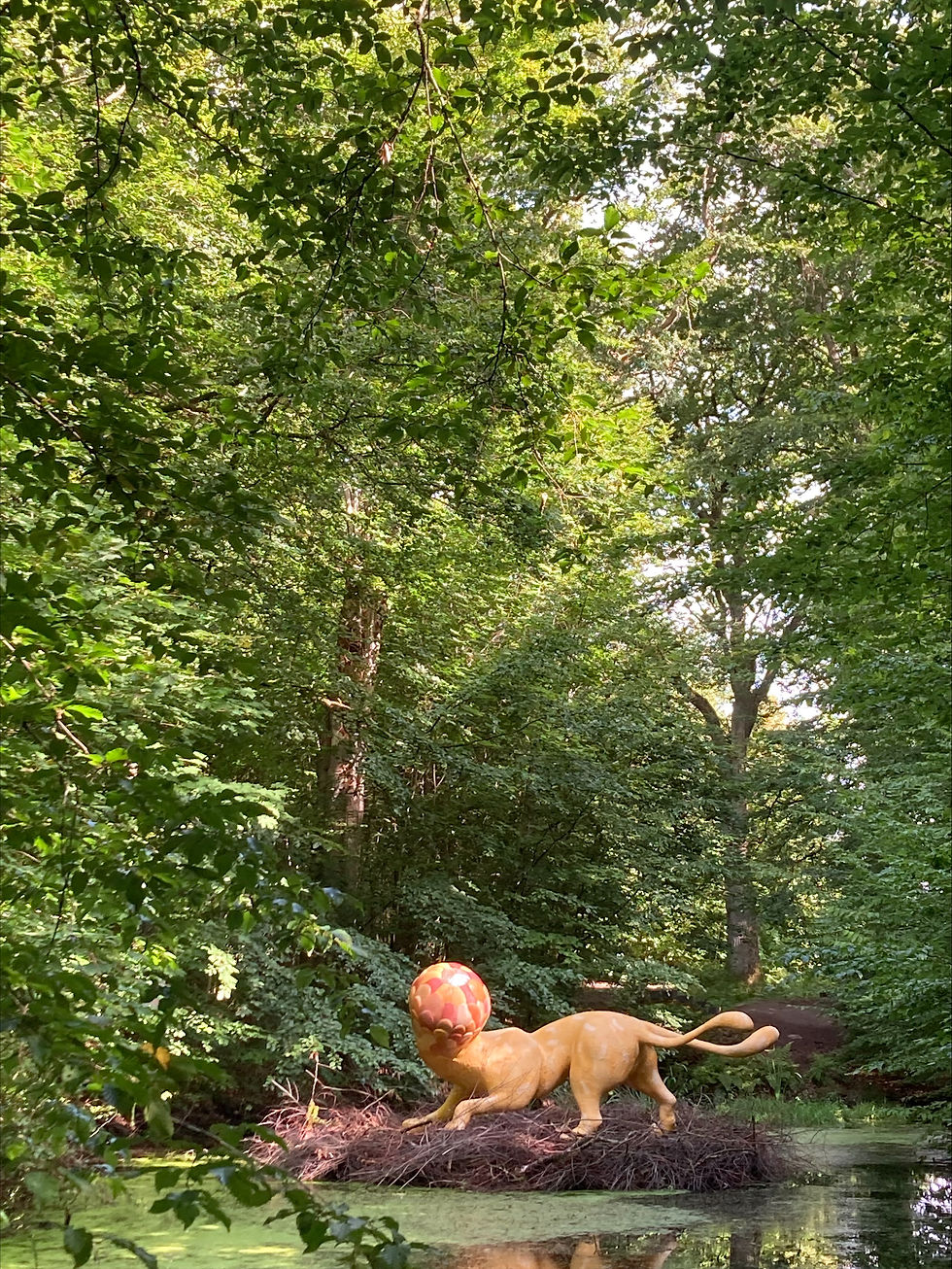

Atang Tshikare

I meet great people during my short stay at Wanås. Zuzana Malina Černohousová is a Czech curator and visual artist who happens to be doing a curatorial research traineeship. She’s here with her daughter for a month and has evidently spent time in the park, surveying its various works. We talk about the major literary art festival in Prague, which she has been part of the team for over a number of years, and I get the scoop on some literary titans she’s encountered through that role. But I also learn about how art in Prague and the Czech Republic is thriving, and how people fear Russia due to history and geographic proximity. These are scary times and, as a curator, my last exhibition of the year is a survey on Neo-Goth in the 2020s, echoing a 1997 exhibition at ICA Boston: Gothic: Transmutations of Horror in Late-20th-Century Art. In the book I’ve brought with me to Wanås, written by The Cure co-founder Lol Tolhurst, I discover how Goth always has a revival in times of societal uncertainty.

I’ve been reading the news on The Guardian and the Associated Press every two hours for months now, but this routine does not continue for me at Wanås. It’s a luxury to soak in the quiet silence here (quiet, because—well, silence can be loud and violent too); and getting lost in art is something that is increasingly hard to do in front of a screen or even inside a lavish gallery. It almost takes a phone without batteries and that inner connectedness felt when encompassed by the beauty and superiority of a natural environment like this.

Ashik Zaman